Madinah Thompson, Natalia Gonzalez Martin,

Eve Stainton

Autumn Residency 2021

Madinah, Natalia and Eve joined us in collaboration with Cob Gallery

THE ARTISTS

ES: I come from a movement and performance background. I work to resist rigid contexts and structures and exist in multi-disciplinary spaces, exploring ideas of queerness and liminality. In the last five years I’ve been doing digital collage using an app on my phone, trying to understand what my choreographic practice is in a digital realm. Most recently, I created a performance piece, Dykegeist, for the ICA. I understand it as world-building, where movement practices are held in between structures and objects. I’m interested in the atmosphere that can be created between things. Movement, because it’s something energetic, which comes from within and spirals outwards, is in conversation with things in the wider world. I was uncomfortable with how the aesthetics of queer performance became recognisable: malleable, slippery things, like gunge or an octopus. To me, that went against the innate idea of queerness as something that can’t be coded or defined. And while I enjoy and support the thinking behind such aesthetics, there isn’t space for those whose physicality relates to something more brittle. So, I have given myself permission to explore that through the prism of queerness.

MFT: I am interested in how Black womanhood is both invisible and visible. My work explores what it feels like, on a granular level and on a day-to-day level, to be objectified and fetishised. I place myself as an object in the centre. It is usually research and text-led; I write poetry. My BA performance piece No Black Girls Sorry was inspired by a man’s Tinder profile. It blew my mind – nothing has changed. I’m still an object, either a Mammy or Jezebel. More recently, I have been researching the experience of being Black in rural UK spaces. An alignment was made between Black people and urban areas: in the States, people moved from the South to the North, in order to reach cosmopolitan areas where they could be freer and safer. But that’s not all Black people are. There are Black people who live in rural spaces – I grew up in Norfolk, we do and must exist. I am examining feeling disconnected from this land, thinking about the sensory access to nature available to me when I am rejected from that space. When I go for a walk on the beach and people make comments, how do I get past that barrier in order to connect myself to what feels intrinsically important? I dislike the word microaggression because no aggression is micro. It builds up. How do you exist, as a person, when you have those push and pull factors impacting your soul?

NGM: I am a painter, but I am trying to expand my practice into space through installation. I want my work to exist out of contemporary time. I have rules for my paintings, one of them is to not include anything that can be linked to today. In this way I’m trying to create a universal language, that includes symbols anyone can relate to. In part, these references are obscure but, at the same time, they are rooted in the history of Western Art, especially medieval or late-medieval representations of how people live. I’m interested in the rules, the commandments and the religion, specifically Catholicism. And in ideas of shame and punishment that come with that. It’s interesting how each action in our day-to-day lives can be related to those religious rituals; even drinking echoes the Eucharist. I use myself to find the figures in my work. During the pandemic, I would take weird photographs of myself in different poses, it wasn’t a conscious choice but I didn’t want to bother my flatmates. That is why all my characters are women, posing alone. And why the perspective between painting and painter has been collapsed: looking at the hand in the painting, you could be looking at your own hand. It’s never far away. You’re in the scene, but also not.

ES: It’s interesting understanding this intimate relationship between yourself, the digital camera and selfie-culture, moves into your paintings, with the depictions of religious iconography. It’s like a performance.

NGM: They are all, in a way, self-portraits, but I’m not that interested in myself. Maybe I’m trying to find a universality through my own experience.

THE WORK

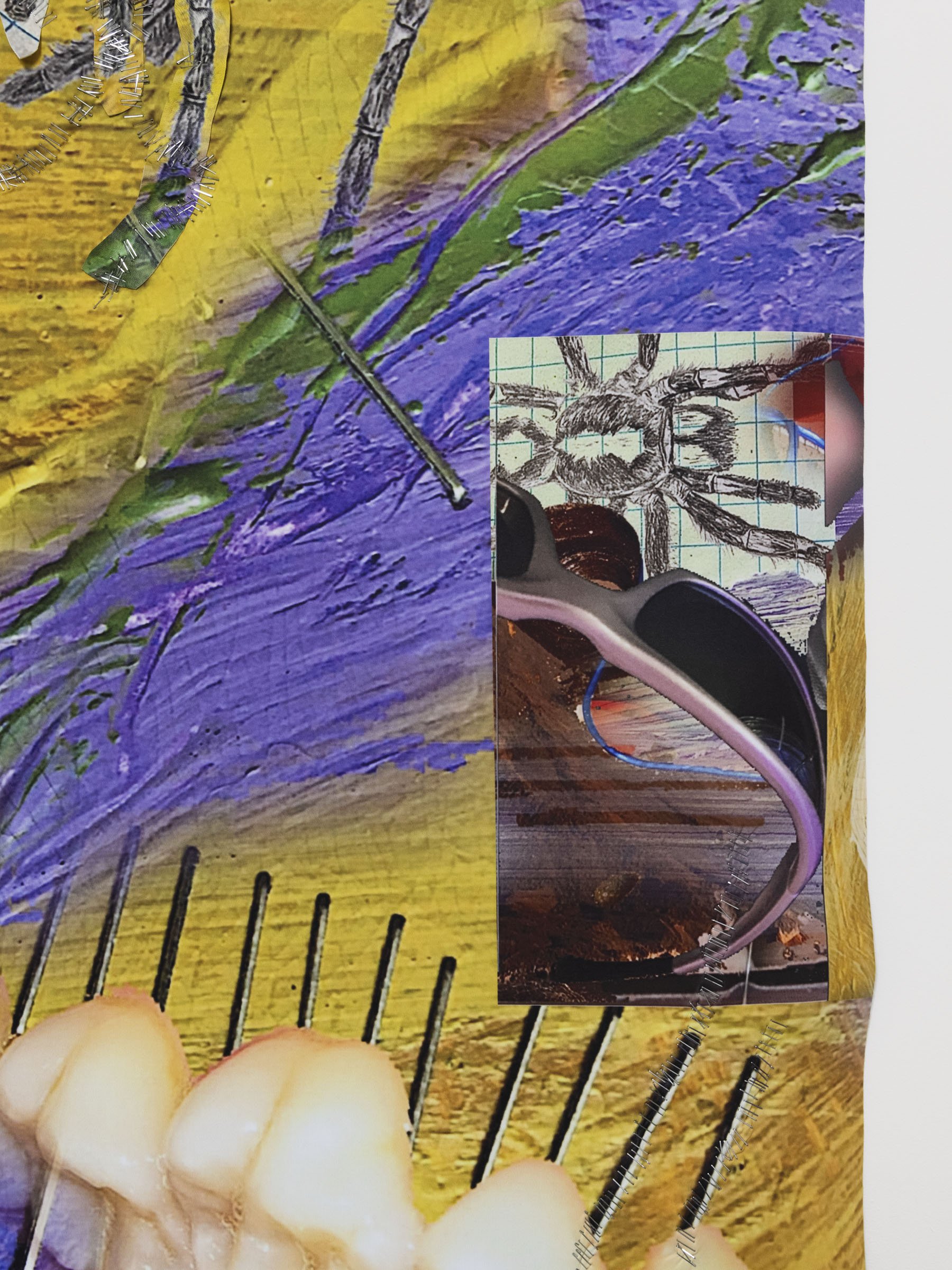

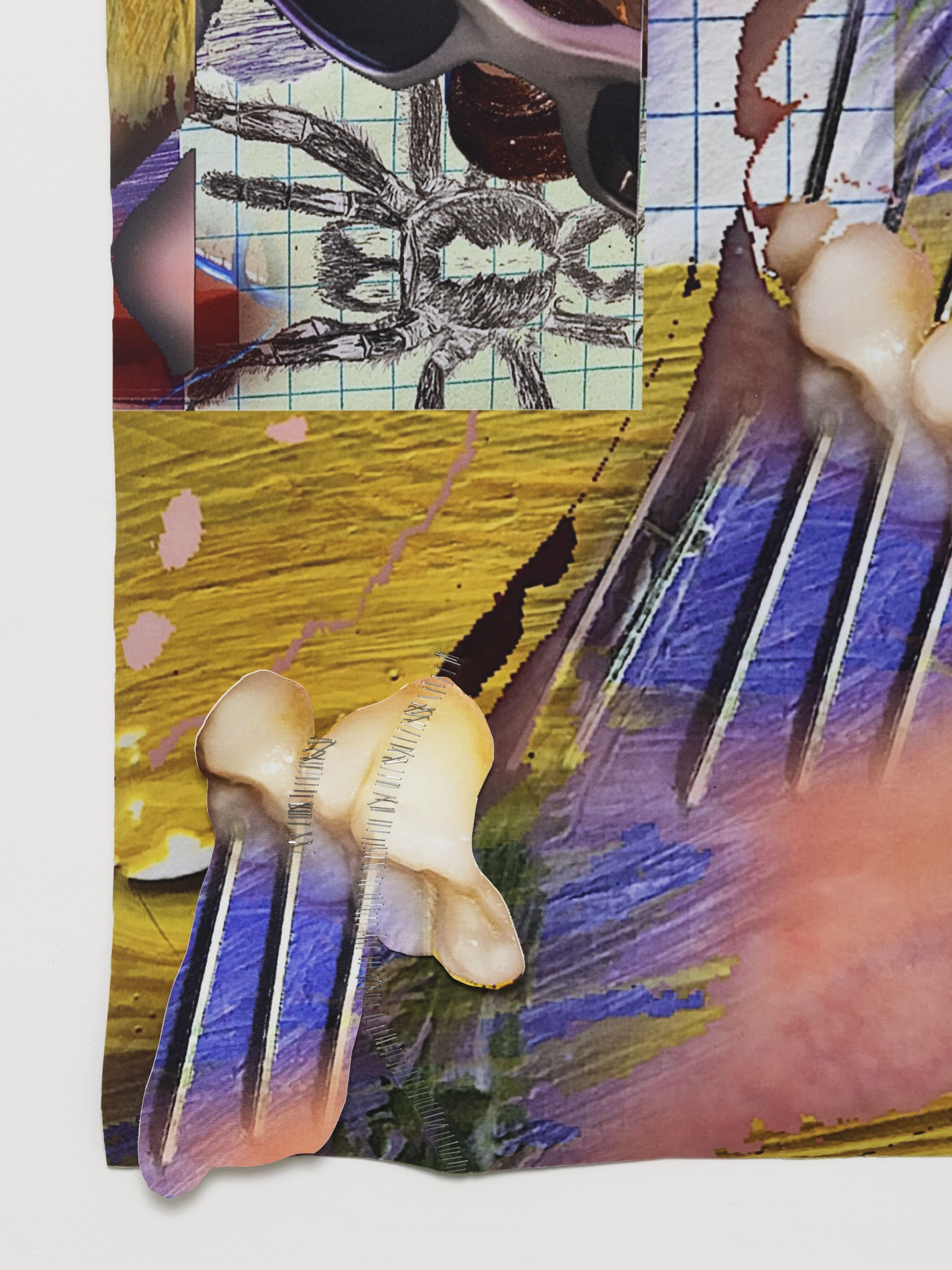

ES: Usually my work begins from a place of imagined performance; I knew that material practices were emerging in the background, but I haven’t had the time and space to focus on them. I have made digital collages and printed them on neoprene: I was excited to think about what these pieces could be in a gallery space. Because I didn’t go to art school, I have never had the time to get granular – what is the materiality of the fabric, what does it mean in relation to the stapling, and then in relation to these relic-type metal objects? Images have been carried over from Dykegeist: the spider relates to phobic symbols, teeth evoke feelings of visceral fear, and the 90s sunglasses reference the disguise I wore. Each relates to the projections that are put on the ‘predatory lesbian’. I was also researching ‘hauntology’, which was originally coined by Derrida, and which, in my creative understanding refers to a displacement of time. Through the figure of the ghost, the past and present and future merge and linear time collapses. This relates to philosophies of movement: what are the histories that I carry through my body? And then again, what new lives can objects take on, what seeps through? Like these metal relic-type objects and these images – both of which have come from my performance.

MFT: I have been working intuitively on the residency, making collages, which is a departure from my usual process. The collages are printed on tracing paper and incorporate texts that I wrote at the beginning of the month. They exist in a body of work titled Call when you reach which is something my paternal grandmother used to say. It means, ‘call me when you get home safely’. I am trying to find where home is. In the collages, my body references a diagram of submissive BDSM positions – I’m interested in what I’m submitting to and whether I can be that vulnerable. What that means from my political position. The thread that runs through all the work is my grandmother. The understanding of mortality that I have comes from holding her hand when she died. It was the most incredible experience of my life. It gave me a different insight into my vulnerability and my capacity.

NGM: I am making installations. I wanted to give context to my work, to gain autonomy over it. My paintings are heavily based in narrative, and I want to communicate that. The installation is moving towards ideas of the chapel: the curtain references those of a small church, used to hide an altar. The petals relate to the natural detritus that is often found in these old spaces. The fountain references holy water. The work is like a Giotto painting, because the space is too

THE RESIDENCY

ES: It has been a critically engaging and active space, and that has been inspiring. I feel like I have learnt from both Madinah and Natalia just through the conversations we have had about our work, and about life.

MFT: It has also been supportive, being able to ask each other’s opinion on something. The energy too: both caring and productive. We all want to do a lot, to push ourselves. And that energy has helped me keep going.

NGM: I like how different our work is. It has been eye-opening witnessing different modes of creation. Madinah starts with words and Eve is experimenting with digital materials – how often to you get to see other people’s approaches to making art? You learn a lot and start unconsciously incorporating their processes.

MFT: When we applied, none of us had studio space.

ES: I was trying to make things in between my bedroom and my housemate’s bedroom.

MFT: Natalia was painting in her room. It’s inspiring to think how our practices have changed both since applying to this residency and while on it. The work that we’ve made is a diversion. It’s a space that has allowed us to explore and push our practices.